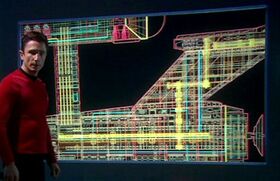

A schematic of the starship USS Defiant (NCC-1764)

The Constitution-class starships, which were also known as Starship-class or Class I Heavy Cruisers, were the premier front-line Starfleet vessels in the latter half of the 23rd century. They were designed for long duration missions with minimal outside support and are best known for their celebrated missions of galactic exploration and diplomacy which typically lasted up to five years.

History[]

The Constitution-class lineage was launched some time prior to 2245, and served as Starfleet's front-line vessels for the rest of the century. The Constitution-class also served as a mighty deterrent to both the Klingon Empire and the Romulan Star Empire, several times taking part in combat actions which determined the fate of the entire Federation if not the Alpha Quadrant itself. [1]

The Defiant in a Tholian drydock facility

In 2267, there were around twelve Constitution-class starships in the fleet. [2] These included the NCC-1700, the USS Constellation, the USS Defiant, the USS Enterprise, the USS Excalibur, the USS Exeter, the USS Hood, the USS Intrepid, USS Lexington, and the USS Potemkin.

The most famous Constitution-class starship was the USS Enterprise (NCC-1701), launched under the command of Captain Robert April in 2245. The Enterprise gained its reputation during its historic five year mission (2265-2270) under the command of Captain James T. Kirk. [3]

In an alternate reality, the Enterprise was launched under the command of Christopher Pike in 2258, [4] while Captain Kirk's five-year mission began in 2261. [5]

In 2266, on stardate 1709, the Enterprise was instrumental in preventing a war between the Federation and the Romulan Star Empire. When a Romulan Bird-of-Prey crossed the Romulan Neutral Zone and destroyed several Earth Outpost Stations, Captain Kirk barely managed to outwit the enemy commander and stop his vessel from returning to Romulus and reporting on the Federation's weakness. [6]

In late 2268, Excalibur, Hood, Lexington, and Potemkin took part in the disastrous testing of the M-5 computer, which had been placed in control of the Enterprise. The Excalibur was severely damaged, with all hands lost. The Lexington also was brutally assaulted by the M-5 computer when the unit became unstable. [7]

USS Enterprise - bridge module in 2265

Later that year, Defiant responded to a distress call from an unexplored sector of space, claimed by the Tholian Assembly. Shortly upon entering the region, the Defiant crew began experiencing sensory distortion, and insanity quickly spread throughout the ship. The ship's surgeon was unable to determine what was happening, and eventually the insanity induced by the phenomenon lead the crew to kill each other. Three weeks later, Starfleet ordered the Enterprise to mount a search mission to locate the Defiant. On stardate 5693.2, the Enterprise located her adrift, lost between universes in a space warp. As a result of a later phaser exchange between the Enterprise and several Tholian vessels, a hole was created through the spatial interphase, pushing the Defiant into the mirror universe. [8]

Unknown to history in the "prime" universe, the Defiant emerged in the 22nd century mirror universe, where the Tholians of that universe had created the interphase rift by detonating a tricobalt warhead within the gravity well of a dead star. [9] The Defiant would seemingly go on to play a major role in Empress Sato's rule over the Earth. [10]

Constellation was lost when the Enterprise crew used the Constellation to destroy the Doomsday Machine in S2.E6.[11]

Refit history[]

From 2254, or earlier, to 2265 Constitution-class vessels featured a large deflector dish, a large bridge dome of semi-spherical shape, and an antenna spike protruding from the Bussard collector cap on each warp nacelle. The impulse drive had two exhaust vents in 2254, and as many as eight smaller vents in 2265. [12] [13]

USS Enterprise - impulse and warp drive in 2265

Sometime between 2265 and 2266, the old deflector dish was replaced by a significantly smaller model, the spikes on the Bussard collectors were removed, a smaller bridge dome of flatter curvature was installed, the aft caps on the warp nacelles were each equipped with a spherical attachment, and the impulse drive now had only two large exhausts. [14]

The interior passageways, main bridge interior and briefing room were already redesigned sometime between 2254 and 2265, and new intercoms were installed.

In 2266, the interior passageways were again modified, the briefing room was completely redesigned, and the overhauled main bridge featured an enlarged main viewscreen and upgrades to the control interfaces and station arrangement, but the overall appearance of the bridge remained relatively unchanged as compared to 2265. [14]

Constitution-refit configuration since 2270s

The crew quarters of the 2254 configuration had the capability of carrying slightly more than 200 crewmembers. [12] In the 2266 configuration, crew quarters could hold a crew complement of over 400. [15]

In the late 2260s to early 2270s, the Constitution-class starships underwent their final major refit program. The actual refitting took eighteen months of work and essentially a new vessel was built onto the bones of the old, replacing virtually every major system. Thus, the Constitution-class continued in service for a further twenty years.

Essential upgrades were made to the Constitution-class' warp systems; the old cylindrical nacelles were replaced with new angular ones and the warp nacelle struts were connected to the engineering hull much closer to the neck than before. The engineering hull roughly retained its original shape – while the original hull was essentially a conical cylinder, the refit was much more rounded.

Constitution-refit configuration aft view

The deflector dish was upgraded, doing away with the "satellite" dish architecture. As for the interior of the hull, the most obvious upgrades were the enlargement of the shuttle deck and landing bay, as well as the addition of a horizontal matter-antimatter reaction assembly and a vertical intermix chamber.

New also was the installment of the double photon torpedo launcher with its rectangular housing in the neck of the vessel. Also, the phaser configuration was changed to channel energy though the warp core. Furthermore, the saucer section was considerably extended (almost 20 meters), while the rest of the surface remained about the same.

Major changes were made to the interior of the Constitution-class starships; many new systems were added and existing ones upgraded. Summarizing, only the internal structure of the saucer and very little of the engineering hull and neck may have survived the 2270s refit. [16]

Some refit configurations had the warp nacelles rotated 90 degrees and included additional hatches along both sides of the saucer. [17]

Technical data[]

Physical arrangement[]

The Constitution-class featured the saucer section-engineering section-warp nacelle layout common to most Starfleet vessels. [12] [16]

Various science labs, numbering fourteen in all, [18] were located in the primary hull in the class' original configuration. An officer's lounge and dining area would be located in the aft superstructure beneath the bridge after the 2270s refit. [16]

The modular design of the Constitution-class allowed for component separation in times of crisis. The primary and secondary hulls could separate where the connecting "neck" joined the saucer, allowing either section to serve as a lifeboat if the other was too badly damaged. If an emergency was confined to the warp engine nacelles, it was theoretically possible to disengage and jettison them while keeping the bulk of the vessel intact. Any hull separation was considered a dangerous procedure and not always an option. [19]

Though not an aerodynamic craft, in emergencies, Constitution-class vessels were able to break orbit and enter a Class M planet's upper atmosphere (and maintain attitude control while passing through it) for a limited period of time, conditional on the ship's ability to re-achieve escape velocity. [2]

Command and control systems[]

The Constitution-class's primary command center, the main bridge, was located on top of the vessel's primary hull, on Deck 1. From here, the commanding officer supervised the entire starship's operation.

The command chair was located in the recessed area at the center of the room, in a direct line with the main viewer. This position was equidistant from all the control consoles that operated specific areas of the ship. Consequently, the captain could be immediately updated on the condition of the vessel or its crew during missions, and orders could be given clearly with a minimum of effort.

The chair was mounted on a circular pillar, attached to a rectangular footplate that was directly anchored to the deck, giving it considerable support during an attack. It was designed to swivel on the support so that the captain could turn to any member of the bridge crew.

Piloting and navigation functions were carried out at the helm console, located in the center of the room, positioned in front of the command chair. This panel consisted of three main sections.

On the left was a compartment which opened automatically to permit operation of the targeting scanner. Next to this was the main control panel, which operated maneuvering thrusters, impulse engines, and fired the ship's weapons. Directly below this panel was a row of eight flip-switches provided to set warp flight speeds.

The central section of the conn panel was fitted with a number of sensor monitor lights, and was dominated by two main features: the alert indicator and the astrogator, which was used for long-range course plotting.

The navigator's station had a control panel for entering course and heading data and the flight path indicator, and supplied information on any deviations or course corrections in progress. It also had controls for the weapons systems.

Other stations on the bridge were provided for communications, engineering, weapons control, gravity control, damage control, environmental engineering, science and library computer, and internal security. All stations were normally manned at all times.

Mounted into the room's forward bulkhead was the main viewscreen. Visual sensor pickups located at various points on the Constitution-class' outer hull were capable of image magnification and allowed a varied choice of viewing angles.

The computer systems aboard the Constitution-class starship were duotronic based. [2] [20]

Upgrades[]

Only one turbolift serviced the bridge of the original configuration Constitution-class ship. In the late 2260s, some were refit with a second lift on the port forward section of the bridge. [21] After the major refit in the early 2270s, the bridge aboard Constitution-class vessels would continue to utilize two turbolifts, but both would be located behind the command chair. [16]

The bridge of the Constitution-class starships were subject to many minor and major cosmetic changes over their many years of service. In particular, the main bridge of the USS Enterprise seems to have undergone considerable changes in appearance. In the late 2260s, along with the added turbolift, the bridge design changed from a segmented flat-panel peripheral station configuration to a completely circular design, including curved overhead view screens, and railings and steps which matched the arc of the circumference. At the same time, an automatic bridge defense system was also installed that obscured the translucent overhead dome, which would not return until the Galaxy class bridge. [21] This marked the beginning of major changes to come which would utilize the updated substructure, most notably, its systems were fully upgraded along with the refit of the early 2270s. [16]

The bridge underwent only a few minor modifications from that point until the destruction of the ship in 2285. The bridge of the USS Enterprise-A, commissioned one year later (in 2286), had mainly cosmetic differences at launch, but, by 2287, it had been drastically upgraded to reflect the advances made in computer control technology.

The bridge module had again been replaced by 2293. The lighter color scheme of the original Enterprise-A bridges had made room for a darker, more militaristic look. [22] [23] [24] [25]

Propulsion systems[]

Aft view of an original configuration vessel

The Constitution-class of starships has been fitted with both lithium and dilithium reactor circuits in the warp drive assembly over its service lifetime. The vessel's standard cruising speed was warp 6, while its maximum cruising speed was warp 8. Warp 9 was also possible for this class of starship, although it was highly discouraged because it was an unsafe velocity.

The USS Enterprise was twice modified to achieve a speed of warp 11. The probe Nomad increased the ship's engine efficiency by 57% in 2267, allowing the ship to reach warp 11, but Kirk persuaded Nomad to reverse its "repairs" because the ship's structure could not stand the stress of that much power, and would eventually destroy the ship. [26]

More extensive modifications made to the ship by the Kelvans in 2268, who were able to produce velocities that were far beyond the reach of Federation science, allowing the Enterprise to safely maintain a cruising speed of warp 11 while traveling through the intergalactic void. [27]

A close-up of the refit configuration impulse drive

The maximum warp speed recorded for this class by itself was warp 14.1, achieved by the Enterprise due to sabotage to the vessel's warp drive system. While the ship itself was not structured to take that speed for any length of time, the Enterprise was able to maintain that velocity for nearly 15 minutes. <refRichards, M. (story); Lucas, J. (teleplay); Wallerstein, H. (director) (1969). "That Which Survives". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 3. Episode 17. NBC.</ref>

The Enterprise also maintained stability at warp 22, while tractored to a ship going warp 32. [28]

Following the 2270s refit of the class, the Constitution was equipped with a linear dilithium-controlled MARA (Matter/Antimatter Reactor Assembly), and a pulse dilithium-controlled assembly was installed by the mid 2290s aboard the USS Enterprise. [22] [25]

The Constitution-class' impulse drive system was a twin-port fusion reactor engine, capable of velocities at least 0.8c. [16] A fusion explosion equivalent to at least 97.835 megatons would result if the impulse engines were overloaded. [29]

Main engineering[]

Main engineering was from where the ship's warp was controlled. All thrust and power systems were primarily controlled from this site, and it is also where the main dilithium crystal reactor was located. Life support was controlled separately from Deck 6. [7] [14] [30] [31] [32] [33]

During the 2270s Constitution-class refit, the interior design of the engineering section was drastically upgraded, featuring the vertical warp core and the horizontal intermix area.

Main engineering was lodged on Decks 14 and 15. Deck 14 was the uppermost level of the engineering hull, and was the anchoring framework for the connecting dorsal and the warp nacelle pylons.

On the forward end of the deck was the engineering computer monitoring room, which encircled the cortical intermix shaft and opens, to the rear, into the engineering computer bay.

Deck 15 housed the main engineering room. Located in the center of the room, and extending for many levels both above and below the deck, was the vertical linear intermix chamber. This complex, radically new design in intermix technology, provided operational power for the impulse drive system and furnished enough additional energy to power all other shipboard systems.

Both matter and antimatter for this chamber were contained in a series of magnetic bottles, which were housed in pods at the base of the intermix shaft. [16]

Tactical systems[]

Forward phasers of the USS Enterprise

During the early 2250s, Constitution-class heavy cruisers were armed with a complement of directed energy weapons, that possessed enough power to destroy half a continent in a concentrated bombardment. In addition, these vessels carried on board laser cannons, capable of operating on energy fed remotely from the ship. [12] [34] [35]

By 2266, phaser banks were standard complement aboard this class of ship. A bank actually consisted of a single emitter and its power supply, though it was common practice to fire two banks at a time and refer to it as a single firing. [14] [29] [36]

Original configuration Constitution-class USS Defiant firing its secondary hull aft phasers

Ship-mounted phaser banks had a range of approximately 90,000 kilometers, and like hand phasers, were capable of being adjusted to stun, heat, or disintegrate visible targets, including objects or beings in space or on a planet's surface at a focus ranging from narrow to wide beam. When only motion sensor readings are available, ships' phasers could be set for proximity blast and bracket the approximate coordinates of the target. [6] [37] [38] [36] [8]

In the original configuration, a battery of four to eight forward phaser banks were located on the lower part of the ventral side of the saucer section. Aft firing banks were located above the shuttlebay on the secondary hull. There were also port, starboard and midship phasers. [10] [6] [36] [39] [40]

A refit Constitution vessel fires its forward phasers

The diversion of all but emergency maintenance power to the shields had the adverse affect of reducing phaser power by fifty percent. [8]

The Constitution-class originally mounted at least six torpedo launchers, one tube covering the aft firing arc. Forward tubes were located in the same area as the forward phaser banks. The aft tube fired from the end of the secondary hull. This combined arsenal was powerful enough to destroy the entire surface of a planet. [39] [41] [42] [43] [10]

Torpedo bay (refit configuration)

After the refit of the 2270s, Constitution-class ships mounted three dual-emitter phaser banks on the ventral and three on dorsal faces of the saucer. They covered the forward, port and starboard flanks. Two single emitter aft banks are above the shuttlebay and four midship single emitter banks are located on the ventral surface of the engineering hull.

Phaser power was increased by drawing energy directly from the warp drive. This increase in firepower had a drawback in that the phasers would be cut off if the main reactor was off line. This problem hampered the USS Enterprise on at least two occasions, one in 2272 and again in 2283.

The post-refit vessels had two forward firing torpedo launchers, though each tube could fire at least two torpedoes before reloading. [16] [22] [44]

Transporter systems[]

Extravehicular transporter to and from the ship was accomplished by a number of transporter systems, which allowed personnel or equipment to be transported over large ranges. The transporter platform featured six pads, which were numbered clockwise, beginning with the right front. A redesigned field generator matrix was mounted into the rear wall of the chamber aboard the refit configuration Constitution-class starships.

Aboard the refitted Constitution-class vessels, the transporter operator stood within an enclosed control pod, which had a floor-to-ceiling transparent aluminum panel through which he or she could view the transport platform. This panel served to shield the operator from the effects of any cumulative radiations emitted by the new transporter machinery, a side effect of the more powerful system.

A door in the standard transporter room wall led to a staging area where landing parties prepared for transporter.

Airlocks[]

Airlock staging area in 2272

Refit Constitution-class starships possessed a number of airlocks permitting direct physical access to the ship. One was located at the aft of Deck 1 on top of the saucer section. Two more were located in the lower saucer section, port and starboard, concealed by sliding hull plates.

These lower two are accessed through staging areas. Four spacesuit lockers line one wall; each containing one suit, providing enough to clothe a standard party of four. A small, locked arms cabinet held phasers; communicators, tricorders, translators, and outerwear were contained in a separate cabinet on another wall. [16]

The next set of airlocks were located on the port and starboard sides of the torpedo bays. The final set were located on the port and starboard sides of the secondary hull at the midline. [16] [22] These airlocks opened into the ship's main cargo bay. There was also a "gangway"-style airlock on the port edge of the saucer section.

Located on the upper surface of the saucer section of the refitted Enterprise were numerous small hatches used for entrance/egress during extra-vehicular activities. (Kirk, Spock, Decker, McCoy, and the Ilia probe use one of these hatches to leave the ship when they arrive at V'Ger's "core".) [16]

Landing bay and cargo facilities[]

Deck 17 was the main access level of the engineering hull. The aft landing bay provided personnel in small craft with a means of entering or exiting the vessel, as did the docking port on either side of the level.

The original configuration of the Constitution-class carried a standard complement of 4 shuttlecraft, some of which were Class F. [45]

The refit configuration Constitution-class starship featured a new landing bay design. A wide range of Starfleet and Federation craft could utilize this state-of-the-art landing facility.

Alcoves on either side of the landing bay provided storage for up to six standard Work Bees, and furnished all necessary recharging and refueling equipment. Additional space was available for the storage of non-ship shuttlecraft.

Just within the landing bay doors was a force field generator unit, which was built into the main bulkheads on either side of the entry area. This field allowed craft to enter the ship, while at the same time retaining the atmosphere and temperature within the landing bay.

Deck 18, the refit configuration shuttlecraft hanger bay, was situated at the widest point of the engineering hull. Much of the deck consisted of open space, as it was the mid-level of the cargo facility; thirty-two cargo pod modules could be stored in the alcoves lining the forward, port, and starboard sides of the bay.

The shuttle hangar had sufficient room for the storage of four craft at any given time. During normal storage situations, these shuttlecraft faced aft.

This deck also housed the vessel's lifeboat facilities. These one-man craft, which escaped through blow-away panels in the side of the secondary hull, were provided for those persons were unable to reach the primary hull in case of an emergency. [16]

Crew support systems[]

Medical systems[]

On the original Constitution-class starships, a sickbay facility was located on Deck 6, which featured an examination room, a nursery, the chief medical officer's office and a medical lab. At least one other medical lab was located elsewhere on the vessel, and was used for biopsy, among other things. Sickbay was considered the safest place to be on the ship during combat. [30] [46]

With the class refit of the 2270s, the medical facilities of the Constitution-class starship were considerably updated. New micro-diagnostic tables were capable of fully analyzing the humanoid body at the sub-cellular level, offering the physician a total understanding of the patient's status.

Another new addition was a medical stasis unit, in which patients whose conditions were considered immediately life-threatening could be placed into suspended animation until the proper cure or surgical procedure could be established. [16]

Crew quarters[]

Crew quarters in the 2260s

Crew quarters were located throughout the saucer section – keeping with Starfleet tradition, Deck 5 housed the senior officers' quarters. On the refit configuration vessels, these staterooms were quite similar to the VIP units on Deck 4, with only a few differences.

Senior officers' quarters on an original Constitution

On starships of the original configuration, the officers' quarters featured two areas, separated partly by a wall fragment. One area was allocated as sleeping area, featuring a comfortable bed, and another as work area, including a desk and computer terminal. Entrance to a bathroom was provided through the quarter's sleeping area. Both areas could be configured to personal preference. [10] [31]

Officers' quarters on a refit configuration Constitution

On Constitution-class vessels of the staterooms of the senior officers were composed of two areas which were separated by a retractable, transparent aluminum partition. The room's entrance opened into the living area. A library computer terminal and work desk were provided here. The room's corner circular nook, normally occupied by a dining booth, could be modified at the officer's request.

The other half of the stateroom was a sleeping area, which held a single large bed that could double as sofa during off-duty relaxation. A transparent door led into the bathroom area. By the 2290s, crew space was at a premium, and the size of officers' quarters was reduced to one large room and crewmen were housed in dormitories with bunk beds. [16] [25]

Recreational facilities[]

Recreation room (refit configuration, 2270s)

Aboard the original Constitution-class starships, there were at least six recreation rooms, which included three-dimensional chess and card game tables. There was also a holographic rec room, which was the predecessor of the holodeck. Also aboard were an arboretum, gymnasium, a bowling alley, a theater, and a chapel. [15] [32] [16]

A typical recreation room (2260s)

On the refitted Constitution-class vessels, recreational facilities were further expanded. One large room in the aft section of the starship's saucer section furnished off-duty personnel with a wide variety of recreational games and entertainment.

At the front of the room was an immense, wall-mounted viewing screen. Beneath this was an information display alcove; five small screens exhibited, upon request, a choice of pictorial histories. A raised platform in the center of the lower level floor featured a diversity of electronic entertainment. [16]

Officers' lounge[]

Officers' lounge privacy area on a Constitution-class vessel of the refit lineage

Located at the stern of Deck 2 aboard the refit configuration Constitution-class starship was the officers' lounge. Here, four huge view ports afforded a spectacular view of the ship's warp nacelles and space beyond.

To the sides, small plant areas held flora from several worlds and a small pool featured freshwater tropical fish. Just forward of this section of the lounge were two privacy areas. In each privacy area, a view screen was mounted into the wall, providing a full exterior tour of the vessel. [16]

Specifications[]

Original configuration[]

Affiliation: Federation Starfleet, Terran Empire

Type: Class I Heavy Cruiser

Active: 2240s - 2270s

Length: 289 meters

Mass: almost one million gross tons

Crew complement: 430

Speed: Warp 6 (maximum safe speed)

Armament: ~12 phaser banks and at least 6 photon torpedo launchers

Defenses: Deflector shields

Refit configuration[]

Affiliation: Federation Starfleet

Type: Heavy cruiser

Active: 2270s - ?

Crew complement: 432 (in 2272); 300 (in 2293)

Armament: 18 phaser emitters, 2 photon torpedo launchers

Defenses: Deflector shields and defense fields

References[]

- ↑ Okuda, M.; Okuda, D; (1999, third edition) The Star Trek Encyclopedia: A Reference Guide to the Future. United States: Pocket Books.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Fontana, D. (writer); O'Herlihy, M. (director) (1967). "Tomorrow is Yesterday". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 19. NBC.

- ↑ Biller, K. (story); Doherty, R. (story); Burton, L. (director) (2001). "Q2". Star Trek: Voyager. Season 7. Episode 19. UPN.

- ↑ Abrams, J. (director); Orci, R.; Kurtzman, A. (writers) (2009). Star Trek. Bad Robot.

- ↑ Abrams, J. (director); Orci, R.; Kurtzman, A.; Lindelof, D. (writers) (2013). Star Trek Into Darkness. Bad Robot.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Schneider, P. (writer); McEveety, V. (director) (1966). "Balance of Terror". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 14. NBC.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Wolfe, L. (story); Fontana, D. (teleplay); Lucas, J. (director) (1968). "The Ultimate Computer". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 2. Episode 24. NBC.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Burns, J.; Richards, C. (writers); Wallerstein, H. (director) (1968). "The Tholian Web". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 3. Episode 9. NBC.

- ↑ Sussman, M. (writer); Conway, J. (director) (2005). "In a Mirror, Darkly". Star Trek: Enterprise. Season 4. Episode 18. UPN.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Coto, M. (story); Sussman, M. (teleplay); Rush, M. (director) (2005). "In a Mirror, Darkly, Part II". Star Trek: Enterprise. Season 4. Episode 19. UPN.

- ↑ IMDB; Star Trek S2.E6 aired Oct 20, 1967

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Roddenberry, G. (writer); Butler, R. (director) (1988; broadcast) (1964; filmed). The Cage. Unaired Star Trek pilot; later aired in its original and remastered form in syndication.

- ↑ Peeples, S. (writer); Goldstone, J. (director) (1966). "Where No Man Has Gone Before". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 3. NBC.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Sohl, J. (writer); Sargent, J. (director) (1966). "The Corbomite Maneuver". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 10. NBC.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Roddenberry, G. (story); Fontana, D. (teleplay); Dobkin, L. (director) (1966). "Charlie X". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 2. NBC.

- ↑ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 16.11 16.12 16.13 16.14 16.15 16.16 Wise, R. (director); Foster, A. (story); Livingston, H. (screenplay) (1979). Star Trek: The Motion Picture. Paramount Pictures.

- ↑ Roman, R. (story/teleplay); Wagner, M. (story); Piller, M.; Danus, R. (teleplay); Beaumont, G. (director) (1989). "Booby Trap". Star Trek: The Next Generation. Season 3. Episode 6. Syndication.

- ↑ Carabatsos, S. (writer); Daugherty, H. (director) (1967). "Operation -- Annihilate!". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 29. NBC.

- ↑ Ehrlich, M. (story/teleplay); Coon, G. (teleplay); Pevney, J. (director) (1967). "The Apple". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 2. Episode 5. NBC.

- ↑ Behr, I.; Beimler, H.; Wolfe, R. (story); Moore, R.; Echevarria, R. (teleplay); West, J. (director) (1996). "Trials and Tribble-ations". Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Season 5. Episode 6. Syndication.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Peeples, S. (writer); Sutherland, H. (director) (1973). "Beyond the Farthest Star". Star Trek: The Animated Series. Season 1. Episode 1. NBC.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Meyer, N. (director); Sowards, J. (story/screenplay); Bennett, H. (story) (1982). Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Paramount Pictures.

- ↑ Nimoy, L. (director/story by); Bennett, H. (story/screenplay); Meerson, S.; Krikes, P.; Meyer, N. (screenplay) (1986). Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. Paramount Pictures.

- ↑ Shatner, W. (director/story by); Loughery, D. (story/screenplay); Bennett, H. (story) (1989). Star Trek V: The Final Frontier. Paramount Pictures.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Meyer, N. (director/screenplay); Nimoy, L.; Konner, L.; Rosenthal, M. (story); Flinn, D. (screenplay) (1991). Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country. Paramount Pictures.

- ↑ Lucas, J. (writer); Daniels, M. (director) (1967). "The Changeling". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 2. Episode 3. NBC.

- ↑ Bixby, J. (story/teleplay); Fontana, D. (teleplay); Daniels, M. (director) (1968). "By Any Other Name". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 2. Episode 22. NBC.

- ↑ Culver, J. (writer); Reed, B. (director) (1974). "The Counter-Clock Incident". Star Trek: The Animated Series. Season 2. Episode 6. NBC.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Spinrad, N. (writer); Daniels, M. (director) (1967). "The Doomsday Machine". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 2. Episode 6. NBC.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Black, J. (writer); Daniels, M. (director) (1966). "The Naked Time". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 4. NBC.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Matheson, R. (writer); Penn, L. (director) (1966). "The Enemy Within". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 5. NBC.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Trivers, B. (writer); Oswald, G. (director) (1966). "The Conscience of the King". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 13. NBC.

- ↑ Bixby, J. (writer); Chomsky, M. (director) (1968). "Day of the Dove". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 3. Episode 7. NBC.

- ↑ Roddenberry, G. (writer); Daniels, M. (director) (1966). "The Menagerie, Part I". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 11. NBC.

- ↑ Roddenberry, G. (writer); Daniels, M. (director) (1966). "The Menagerie, Part II". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 12. NBC.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Armen, M. (writer); Taylor, J. (director) (1968). "The Paradise Syndrome". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 3. Episode 3. NBC.

- ↑ Harmon, D. (story/teleplay); Coon, G. (teleplay); Komack, J. (director) (1968). "A Piece of the Action". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 2. Episode 17. NBC.

- ↑ Ralston, G. (writer); Daniels, M. (director) (1967). "Who Mourns for Adonais?". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 2. Episode 2. NBC.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Brown, F. (story); Coon, G. (teleplay); Pevney, J. (director) (1967). "Arena". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 18. NBC.

- ↑ Fontana, D. (writer); Pevney, J. (director) (1967). "Friday's Child". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 2. Episode 11. NBC.

- ↑ Hammer, R. (story/teleplay); Coon, G. (teleplay); Pevney, J. (director) (1967). "A Taste of Armageddon". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 1. Episode 23. NBC.

- ↑ Fontana, D. (writer); Pevney, J. (director) (1967). "Journey to Babel". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 2. Episode 10. NBC.

- ↑ Gerrold, D. (writer); Sutherland, H. (director) (1973). "More Tribbles, More Troubles". Star Trek: The Animated Series. Season 1. Episode 5. NBC.

- ↑ Nimoy, L. (director); Bennett, H. (writer) (1984). Star Trek III: The Search for Spock. Paramount Pictures.

- ↑ Roddenberry, G. (writer); McEveety, V. (director) (1968). "The Omega Glory". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 2. Episode 23. NBC.

- ↑ Lucas, J. (writer/director) (1968). "Elaan of Troyius". Star Trek: The Original Series. Season 3. Episode 13. NBC.